|

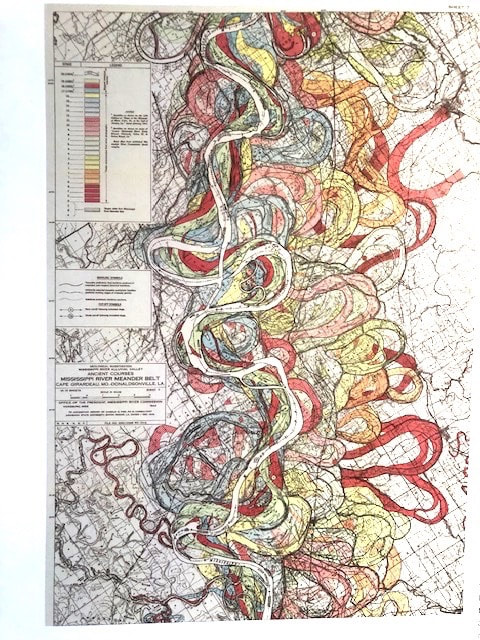

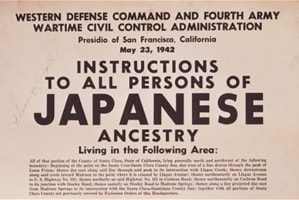

On a recent trip down the Mississippi River from its source in Lake Itasca in Minnesota to where it debouches into the Gulf of Mexico near Venice, Louisiana, I discovered that following the river reveals a more complete and complex story of race and the racial fault lines that divide this country than the one told along the Mason-Dixon Line. Starting from the top, stories of broken treaties, genocide and the forced removal of American Indians dot the river on both sides up and down, the main law being the Indian Removal Act of 1830 which essentially made the entire river the demarcation line for this federal policy. In the middle, the grave of Dred Scott lies on the Missouri side of the Mississippi at the Calvary Cemetery and Mausoleum in St. Louis. In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court ruled that no person of African descent could claim US citizenship, thus freedom, despite having lived for four years outside of Missouri, in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal. Just across the river, the remains of the Cahokia Mounds Indian Civilization, an urban center as big as London which existed in the 13th century and considered one of great cities of the world by archeologists, lies virtually unknown on the Illinois side. Further down the river into Tennessee, you will find The Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, the site where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated as he stood on the balcony on April 4, 1968 at 6:01pm, CST. Move a bit further down and back onto the Arkansas side of the river and you will find two of America’s concentration camps, which imprisoned nearly 17,000 US citizens of Japanese ethnicity during WWII in the towns of Rohwer and Jerome. As a result, the two briefly became the 4th and 5th largest cities in the state. Smack in the middle of the two camps, which are located 26 miles apart from each other, is a museum dedicated to telling the story of what happened there in the town of McGehee. Another story, as you follow the flow of the river out into the gulf from Venice, LA, is the ironic story of Cat Island, Mississippi, where the US military used dogs to conduct a secret experiment on Japanese American soldiers during WWII in the misguided belief that “Japanese” smelled different from other human beings. It didn’t work. The dogs attacked whites just as viciously. On a side trip to Oklahoma, we learned about one of the earliest Native American Civil Rights leaders in the country in the case Standing Bear v. Crook. The ruling established for the first time, in 1879, that Native Americans were human beings. The case was tried in Omaha, Nebraska, on the Missouri River, a tributary of the Mississippi. The struggle to be recognized as human, as well as the right to naturalize and become a citizen and have one’s needs and one’s contributions known, is without a doubt more varied in hue along the Mississippi than the black and white, North and South, struggle most Americans learn. Much of what is happening today with US citizens being detained just for speaking Spanish, or Vietnamese, who were given refugees status at the end of the Vietnam War, being deported after 40 years in this country, has at its core the question, “Who is an “American?” This brings us to the 1790’s Naturalization Act, one of the earliest laws passed by the new continental congress, which established who was eligible to naturalize and thus become an American. It stated that “Any Alien” being a white person…who had residency in this country for two years and was of good character, could become a US citizen. In other words, the first exclusion was the native born…Native Americans. It has been used many times to exclude entire groups of peoples. As I learn more about my country, I see how little many of us, including myself, know about this place we call America and about each other. We, on the East Coast of the country, probably know more about what happened to Europeans in Europe than we know about the formation of the United States and the laws that keep this experiment going. Prejudice, bias and discrimination will always exist, but if it is codified into law, it becomes a form of eugenics. If we are to remain a country based on the rule of law, dedicated to a just and equal world, the only way to achieve that is not only to have our laws reflect that goal but that those laws be equally applied. Drug laws that incarcerate African Americans who use, but provide rehab for whites, is an unequal application of the law. A recent poll shows that 40% of Americans believe that no American Indians are alive and in existence in America today. This prompts the question, if no one hears you, do you still exist in a representative democracy? This poll seems to suggest that the answer is No. Perhaps the Mississippi River and the story it tells of American racial apartheid and the fight to be included could help change all that.

6 Comments

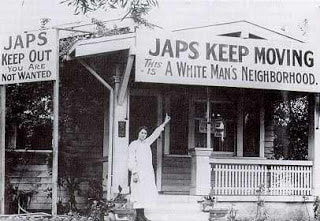

Recently, a New Zealand film crew came to our house to shoot a documentary. While they were setting up, one of the producers began asking about the divisive mood here in America and how he was really surprised to see a truck proudly streaming a confederate flag from the back of its cab as it sped past them on Route 8 near our house in Massachusetts. While it’s still rare, one thing is clear: the confederate flag is not just a “southern” thing anymore. The following two articles talk about confederate flags on display in northern states: Some White Northerners Want to Redefine a Flag Rooted in Racism as a Symbol of Patriotism Confederate Flag at Great Barrington School Prompts Free Speech, Student Privacy Debate The first one basically says that some white northerners are adopting the confederate flag, with its white nationalist roots, as a symbol of white collective grievances and rebellion. The latter talks about a student at a local high school in the Berkshires who wore a confederate flag to school. The ACLU of Western Massachusetts defended his right to do so in the name of free speech. My Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project also speaks to issues of freedom—or what had been the lack of it—for a small minority. The local ACLU defended this boy's right to speak, however, it decided earlier this year that they were not interested in having me talk to their group regarding my question, “Who’s an American?” Perhaps they were too busy with other issues. Perhaps they were the same issues that made them turn a blind eye to this story decades ago...when the National ACLU sided with FDR and his decision to remove the civil liberties of US citizens of Japanese ethnicity 75 years ago. Anti-Asian history rarely gets included in the story of America but for the record, the FFF/YBP has been invited to places like the FDR Library, the Norman Rockwell Museum and the Supreme Court, to name a few. However, since Mr. Trump became President, there seems to be a renewed effort to "sweep" this story under the proverbial rug. To give you some examples, my work was first invited then excluded from: the NY Historical Society and CUNY’s Roosevelt House in May of 2018 (despite being told not three weeks before the opening that my project would be part of a section called Freedom’s Legacy in an exhibit about FDR's Four Freedoms); a panel discussion scheduled to happen in 2018 at CCNY (canceled without explanation); a display of my tea bowls by the reflecting pool at the Clark Art Museum in Williamstown, MA, as part of an art and education program, greeted with great enthusiasm at first, only to end in a polite “not at this time". I have received suggestions to speak on New England Public Radio which never materialized. And perhaps most mysterious of all was the reason I was given why NPR's All things Considered declined to feature my project for the 75th anniversary of FDR's Four Freedom's Speech or the 75th anniversary of the signing of EO 9066. Even as a travel piece it could have worked, as there are not many people who have actually been to all ten of America’s WWII concentration camps. Their reason, I was told: my family was not in the “camps.” Most people say that my project belongs at the Asia Society or, even better, at the Japan Society. And yet, I submit that this history (a pattern of discrimination spelled out in hundreds of pieces of anti-Asian legislation passed in this country that spans almost a century from the 1870’s -1960’s) provided a clear road map to the present—a modern example of a deliberate pattern of exclusion which continues to affect people of color to this day. That pattern of "the other," I believe, has its roots in the 1790 Naturalization Act and its assertion that “Any alien, being a free white person” who had been in the US for two years was entitled to be called an American—and nobody else. "Any alien” meant that the first exclusion was the native born: Native Americans. This law has been used time and time again to exclude persons deemed not white, despite numerous updates to said law, and in spite of the guarantees provided by the Constitution, implied by the Declaration of Independence and reinforced by the Emancipation Proclamation. While we say “Justice for All,” the reality has been Four Freedoms guaranteed for some. The targets of exclusion may vary, but if the rising popularity of the confederate flag is any indication, the importance of “whiteness” seems to remain an essential element of “Americanness,” maybe not to all, but to enough of us to matter. Barbara Takei, the head of the Tulelake Committee, asked me to share this latest update on the effort to save Tulelake (CA), considered one of the most important of the ten sites where US citizens of Japanese ancestry were mass imprisoned during WWII. The Committee hopes to preserve the lessons of yesterday for tomorrow’s generation.

"The Tulelake airport land occupies 2/3rds of the area where more than 24,000 Japanese Americans lived and where over 331 died during the years of incarceration from 1942 through 1946. In the postwar years, homesteaders desecrated the concentration camp’s cemetery by bulldozing it, leaving it as a gouged-out hole in the earth. The burial earth was used to fill in the grid of ditches within the concentration camp site so the historic site could be used for an airport.” The Tulelake committee’s bid to buy the land, which was more than double the price of what it was sold for, was ignored. Instead... "The City of Tulelake sold the land to the Modoc of Oklahoma, who have been under investigation for misusing their tribal sovereignty to help usurious payday loan businesses avoid government regulation. By the time of the sale, City leaders knew of the FBI investigation, IRS investigation, FTC investigation, Federal convictions, and over $4 million in penalties paid by the Modoc of Oklahoma. According to local news reports, City leaders dismissed the Oklahoma Tribe’s misconduct after assurances by the Oklahoma Tribal leaders. At the City’s meeting to sell the airport land, a lawyer for the Oklahoma Modoc tribe, Patrick Bergin, assured City Council members that the Oklahoma Tribe would not support the local Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin Tribes’ pending lawsuit to protect sacred fish and wildlife habitat." Here is the whole report. If you would like to help, contact: Tule Lake Committee v. City of Tulelake, et. al. For information, contact: Barbara Takei [email protected] 916-427-1733 . . .or I should say 40 minutes north of Boston, where “Yellow Peril” and the "Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project” will be at the Pingree School, in South Hamiliton, MA. If you're in the area, come join me for a reception to "meet the artists" on September 16, 2018 at 1pm.

The Supreme Court officially overturned the wrongful 1944 ruling on Korematsu vs. the US this week (Tuesday, June 26, 2018), but cleared the way for an ethnically based Travel Ban which hints of 1882 and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Justice John Roberts acknowledges the wrongful use of concentration camps to imprison US citizens on the basis of race and officially overturns the offending law with the following phrase: “Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority,” Roberts wrote. “But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission.” Here’s the complete story. While it corrected a 74-year-old wrong, it replaced one long held injustice with another by legalizing the use of a travel ban on an entire ethnic group or country, echoing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The passage of that law would usher in a host of exclusionist laws targeting people of Chinese ancestry in this country, then Japanese immigrants and their children and eventually to all Asians in general. While most laws have been repealed or been canceled out by other laws, the fact that Korematsu remained technically on the books until this past Tuesday means discriminatory actions taken against Asian peoples have been not just accepted but ambiguously legal for over 130 years. This is probably why the Asian American experience is seldom included in discussions about the history of American Jurisprudence because it was legal. I was recently invited to participate on a panel discussion on WAMC—my local NPR Station—about immigration, to ask the question which is at the heart of my project…Who is an American? And what does citizenship mean? While that question and its answer may be clear for some in the eyes of the US government, it has not always been so straightforward for folks who looked like me and my family. On another related note, documentary filmmaker Vivienne Shiffer, who grew up in the community adjacent to one of the two concentration camps located in Arkansas and produced the film, Relocation, Arkansas, the Aftermath of the Incarceration, sent me this report from the Arkansas Times: [One clarification that needs to be made—this proposed site is not 5 miles from the Rohwer Camp site: it is not only adjacent to it, 160 acres of the proposed site is land that actually comprised part of the Rohwer Camp.] Proposed child holding site in Arkansas 5 miles from WWII Japanese-American internment camp Posted By Benjamin Hardy on Thu, Jun 21, 2018 at 2:39 PM THV 11 reports that the Trump administration is considering a piece of property in the unincorporated Desha County community of Kelso in its search for sites to house immigrant children forcibly separated from their parents at the border. Kelso is about a five-minute drive away from the Rohwer internment camp at which over 8,000 Japanese-Americans — many of them children — were held captive by their own government during World War II.

Here’s the link to the rest of the article. Hope you find it interesting! image: Edel Rodriguez Whether we like to admit it or not, being white, and a man matters in the United States and that’s because early on in the establishment of this country, the rules of naturalization and who could become a citizen (and therefore vote) was codified into law in one of the first pieces of legislation passed by the nascent US congress in the Naturalization Act of 1790, which said that citizenship was restricted to “any alien, being

a free white person” who had been in the US for two years. “Any Alien” was stipulated to exclude Native Americans. The politics of “exclusion” was always at the heart of this new country, although at the same time and ironically it's leaders preached Justice for All. We can now see that they meant Justice for all aliens...but only if they are men, and only if they are white and for good measure, only if they had been here for two years. These words and stipulations have changed over the decades, like the two years to three or more, or to include aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent in 1870. But what about Asians and Asian Americans? I could not have answered that question six years ago. But I can now. What’s most instructive about the Asian American experience today is that it shows how easily hard-won rights can be lost and that the issues of discrimination are not necessarily divided along republican vs. democrat, conservative vs. liberal or even black vs. white. Below is an excerpt from an essay I was asked to write about this aspect of US history for The Washington Spectator. I hope you find it interesting: I recently went to Ellis Island on a beautiful spring morning and spent a couple of hours by myself watching the light pour into the Great Hall before the museum opened to the public. I was there to arrange the most recent iteration of an art project I’ve been working on for several years, this one having to do with an historic event that happened at Ellis Island back in 1942 and a related incident in 1998. To be there all these years later, knowing what I know now, was as if someone had firmly screwed in a light bulb that had been left loose, finally illuminating a part of my story and that of an America that I had never known or fully understood. I was born and bred in the United States and grew up in the 1960s. My immigrant parents, by any standard, had achieved the American dream, with a successful small business in New York City and a middle-class home in the New Jersey suburbs. Like most of our European immigrant neighbors, I felt we were a healthy part of this “melting pot” we called America. My father, out of gratitude for his new country, always drove an American car, a Buick Le Sabre for him and a Dodge Dart for my mother, followed by successive generations of GMs, Chryslers and Fords over the years, despite the fact that many of our neighbors were starting to buy Japanese cars in the ’70s and German ones in the ’80s. My father taught us to appreciate the diversity and generosity of this country, and I remember the pride and excitement I felt being taken to see the Statue of Liberty as a youngster. As we stood on the windswept deck of the ferry, I imagined my parents as part of the great wave of people who were welcomed into the arms of this beckoning green lady. What I did not know at the time was that when my father first arrived, he was not allowed to stay in this country. That’s because he was Asian and, in particular, Japanese. I did not know, growing up, that Japanese people had been banned from immigrating to America, a ban that was in place nominally from 1907 and definitively, with the Asian Exclusion Act (which banned all Asians), in 1924, and wouldn’t truly be lifted until 1965... You can read the rest of the essay The Washington Spectator. To learn more about the Ellis Island Exhibit in 1998, click here. Image: Robin Lee I was asked to write an essay about the Asian American experience for The Washington Spectator. Here’s an excerpt. I hope you find it interesting.

Counting Asians April 16, 2018 By Setsuko Winchester The Olympics have come to a close, and in their wake I’ve been thinking about a stubborn phenomenon that was illustrated most recently by the flack a New York Times columnist named Bari Weiss received after tweeting: “Immigrants get the job done,” together with a picture of Mirai Nagasu, the U.S. ice skater who won a gold medal. Many asked: What do you mean, immigrant? She’s an American. Weiss defended herself by observing that Nagasu’s parents are immigrants. Well, if the standard at the Times is to identify you by your last immigrant relation, then we should take into consideration the immigrant parents and forebears of a lot of our newsmakers, most notably those presently in the White House. We should recognize Trump’s German and Scottish immigrant background, along with that of his Yugoslavian (now Slovenian) immigrant wife and former–Soviet Bloc Czechoslovakian-Scottish-German-immigrant sons and daughter. And how about the Belarusian-Jewish son-in-law, whose family escaped the Holocaust? When you see things the Weiss way (who I’m assuming, by the name, is a German-American immigrant), I think it’s strange that the Times doesn’t question Trump’s “American” bona fides or for that matter his America First policy, with its demands to close the doors on “immigrants,” since his presidency is clearly an example of the rise of the recent immigrant. Rather than hide it, as if it were something to be ashamed of, shouldn’t the White House celebrate how wonderfully open and generous America has been to his immigrant family? You can read the rest here. Twenty years ago, on April 3, 1998, an exhibition opened on Ellis Island which explained the difference between two types of government facilities used in the US during WWII to imprison citizens and non-citizens of the US. It poses the question..what do you do if your government turns against you, not for what you did…but for what you are? And did having US citizenship matter? In the 1940’s, the answer was no. There is a term for that kind of imprisonment... Ellis Island US Internment Camp - A Matter of Due Process - vs. Manzanar, CA US Concentration Camp - A Form of State-Sanctioned Racism - One tea bowl = 1,000 individuals Image 1: “Ellis Island - 16 tea bowls” Over 31,000 individuals were rounded up and put in internment camps run by the DOJ and the INS. These Individuals were mostly foreign nationals. Those imprisoned in these facilities were arrested with charges and given a hearing. If they were unable to prove their innocence, they were held until deported. These facilities were protected by the Geneva Conventions. This was legal. 11,500 German foreign nationals 3,000 Italian foreign nationals 16,500 Japanese foreign nationals (most were released to one of the ten US concentration camps) Image 2: “Manzanar, CA - 120 tea bowls” The US concentration camps were run by the military and administered by the WRA. Anyone with 1/16th Japanese blood in the western half of the western states (where most of them lived) were rounded up (even orphans in orphanages) and imprisoned for the duration of WWII. No one was ever charged, given a trial or hearing, and the prisons were not protected by the Geneva Conventions. This was not legal. Concentration camps are historically a very specific kind of incarceration which has been used as a tool of empire. It’s the imprisonment of a concentration of a particular group of people solely for who they are, not for what they did. FDR helped promote universal human rights and yet removed the rights he said were a basic part of all Americans’ lives from certain citizens, most of whom had been in the US for multiple generations and who had committed no crime. There is a historic pattern of “removing the other” in America. It continues to happen today. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/confirmed-the-us-census-b/ A friend just sent this to me. If you read the latest books about the roundup of Japanese Americans, this information is in there, but as we know these kinds of books are not read or reviewed…it seems as a rule. But even when it’s in a publication like Scientific American, this kind of American history never gets into the "lay-readers’” diet of information that is fed to them by the purveyors of “general interest” news organizations as the NY Times has recently described itself and its readers to me in a correspondence with their Standards Editor about a similar matter. "Thanks for this additional background. I definitely don't discount or minimize the importance of the topic or the need for historical accuracy. I do find, though, that in many areas there is a gap between the precise legal or historical terms used by experts and the ordinary terms used by laypeople to describe the same things. The best terms for a historian writing a scholarly paper wouldn't necessarily always be the best usage for a general-interest newspaper." In trying to find this story in the NY Times, I found this from Dec. 2017 under the category “Lesson Plans/US History”: Teaching Japanese-American Internment Using Primary Resources As we are teaching history: Lesson one: Headlines matter. It would probably be more accurate to say the US forced roundup and mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans. Lesson two: Internment was used not to detain Japanese Americans, but to imprison Germans, Italians and Japanese foreign nationals (and some of their children and spouses). Lesson three: Japanese Americans were not placed in Japanese Internment Camps, but in what we now know were called US concentration camps by FDR and his administration. I didn’t know what to expect when we got to the first camp…which was Rohwer, in Arkansas. It had a cemetery and a memorial and a row of kiosks to explain what happened there in what is now row after row of flat agricultural farm land, perhaps cotton? Most everything had been harvested. It was pretty warm and it was December. We just had a rudimentary map and just sheer determination to find all these places. For a city girl who’s lived in NY City, Washington, DC and a year and a half in Tokyo, going to these sites gave me a new insight into my country, what democracy means and what life can be like for folks who don’t live in areas with every amenity available to mankind. Even living in a tiny, sparsely populated rural town in the Berkshire Mountains of MA didn’t prepare me for the sense of isolation at some of these locations, often a vastness which could seem deadly but beautiful at the same time. The journey also tells a different story of America and Americans (white, native American, Latino and black, rural and remote) than what I was used to, a story which seems more relevant today than when it happened 75 years ago. Back then we didn’t know or didn’t want to know. Today, to do the same would be to return to those days...of looking the other way. On a brighter note, the journey of looking for these places will also take you near some spectacular geological landscapes like the Grand Canyon, the Petrified Forest, Yellowstone or Crater Lake, depending on how you’d like to connect the dots. At almost all of these sites, people have taken care to rebuild, resurrect or preserve a part of the history there. A few have amazingly well put together interpretive centers while others are in the process. To let them disappear would be a shame because it means we will lose an essential part of this country's story, the struggle to become an American, which is central to understanding who we are as a nation. Although the deadline for the Call to Action has passed, I thought I’d share this with you. JANM is joining Japanese American organizations across the nation in an important call to action to help support continued funding for the Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program. Please consider lending your support by contacting your elected representatives. Call to Action Tell Your Representative to Support JACS Support the continuation of funding for the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program (JACS) by contacting your representative! JACS funding is vital to the preservation of the legacy of incarceration endured by Japanese Americans during World War II. This funding is used across the nation in many capacities, such as art, education, and recording of oral histories. Rep. Doris Matsui is leading a Dear Colleague letter that expresses support for continued JACS funding. We are asking for your help by contacting your representatives and asking them to sign on to Rep. Matsui’s letter. This will show that you, as their constituents, care about this funding. The deadline for the letter is March 16th, so act fast! Also, if you or your family has any connection to a specific incarceration camps, please consider contacting the Representative of that camp’s location. Below is a list of each camp and the Representative of that area. Please use the samples below to get in touch and show your support! Camps by District and Representative Jerome and Rohwer—Rick Crawford AR-1, French HIll AR-2, Steve Womack AR-3 Granada Amanche—Ken Buck CO-4 Topaz—Chris Stewart UT-2 Gila River—Krysten Sinema, AZ-9 Poston—Martha McSally, AZ-2 Tule Lake—Doug LaMalfa CA-1 Manzanar—Paul Cook CA-8 Minidoka—Mike Simpson ID-2 Kooskia Work Camp—Labrador ID-2 Heart Mountain—Liz Cheney Sample Email Dear … : I am writing you today to ask for your support of the Japanese American Confinement (JACS) Program. JACS was passed in 2009 with bipartisan support and has funded many important programs. Preserving Japanese American history is important to me because … I have personally benefited from JACS through … (list program and its importance to you). I am asking you to sign on to Rep. Matsui’s letter to the appropriations committee in support of JACS. Any questions can be directed to Andrew Heineman of Rep. Matsui’s office at [email protected]. If you are unable to sign onto the letter, I ask that you consider including JACS funding in your individual appropriations requests. Thank you for your time, Additional Reasons to Highlight

Sample Phone Script Hi, my name is … and I am a constituent. I am asking Rep. … to support continued funding for the Japanese American Confinement Program. This program is important in educating the public about Japanese American incarceration and preserving this chapter in America’s history. I personally support JACS because … I ask Rep. … to sign onto Representative Matsui’s Dear Colleague letter or to submit an individual request for the continued funding of it. Thank you for your time.

|

Setsuko WinchesterMy Yellow Bowl Project hopes to spur discussion around these questions: Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? How long do you have to be in the US to be considered a bonafide member of this group? Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed