|

I recently wrote the essay below for my local Massachusetts paper, The Sandisfield Times, at the encouragement of the editor, Bill Price. The essay examines many of the laws that lie outside the strictly Black/White paradigm to bring focus to the lesser known grey area of law which governed those who are legally “not-White”. Out on the Limb of History...When Most Asians Disappeared The report about the Sandisfield Arts Center’s 2019 program last month was a lively column about how

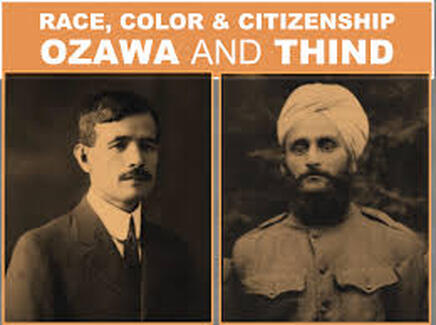

Sandisfield’s Art Center strives to educate us about “Our Town,” our constitution, and our history. Featured were “Stimulating and timely talks from our scholars Bill Cohn and Val Coleman (Val paid for copies of the U.S. Constitution at his inspiring and passionate lecture, ‘The Constitution Alive’) and Dr. Robert Maryks presented ‘Fascism and Racial Laws in Italy’ (preceded by a free showing of ‘The Garden of the Finzi-Continis’).” It’s good that we learn the history of fascism and race laws around the world and re-examine what the constitution says, but shouldn’t we also learn about one of the most legally racist periods in US history – the post-Civil War/Reconstruction era between the 1880s and 1940s? During this period, when the U.S. was opening vast swaths of territory to “settle,” hundreds of local, state, and federal laws were written and passed which would legally define who could and who could not become an American and thus receive constitutional protections as well as participate fully in our country’s democracy. Back then it was a white minority fearing being overwhelmed by a non-white majority. During that time a fearful electorate passed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, banning further immigration from China. This act would inspire the creation of a new federal agency, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which became a new arm of government created to enforce the new exclusion act. A quick look at U.S. race laws that followed show that “not white” was chosen as the quick and easy way to separate the chaff from the desired “all-American” wheat. Those who did not fit in with this paradigm were left to fight it out through the courts which, more often than not, ignored the constitution’s call for liberty and justice for all and instead confirmed and expanded this country’s racially-based caste system, cementing it firmly into the laws of the land. Most discussions on race today remain limited to a white/black paradigm but it’s the hundreds of laws targeting other “non-white” peoples passed after the Civil War which still linger. Their effects continue to enliven our political discourse today. While many of us in this country come from Europe, many of us did not. Many were already here and had a different row to hoe towards “freedom, liberty, opportunity, and justice.” In fact, it was post-1880s that a whole new category of human beings was slowly shaped, molded, and defined by the rule of law – those deemed to be “Aliens ineligible to naturalize.” (This would not include my husband, who is white, British, Christian, and an immigrant, but would have – had I not been born here – excluded me.) These laws were all based on the 1790s Naturalization Act – which stated that “Any Alien”... being a ‘free white person’... having had residency for two years ... was of good character ... could naturalize.” The phrase “Any Alien,” of course, excluded native born Native Americans, the first to be excluded. And a look at the long history of “Exclusion” laws shows how important that one adjective, “white,” written into that early law by the founding fathers helped to tint the color of our laws and our citizenry ever whiter for nearly 150 years. What we’re seeing today is less “Garden of the Finzi-Continis” and more a continuation of the Page Act of 1875, the Dawes Act of 1887, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. And In re Saito, 1894, was the first law passed in the U.S. to specifically exclude persons of Japanese ethnicity from becoming an American citizen, the court having ruled that because Mr. Saito was “not white” he was ineligible to naturalize. By 1922, it would become a federal law (Ozawa v. US) with the Supreme Court’s ruling that a Japanese person was “not white,” therefore could not be a naturalized citizen. As a resident of the Berkshires, it was a bittersweet realization for me to discover that the Saito ruling was made in a district court right here in my adopted state of Massachusetts. The legal rationales were congressional intent, common knowledge, scientific evidence, and legal precedent. Maybe that’s why even after having gotten a graduate degree in Journalism from NYU, worked for 10 years as a journalist at NPR headquarters in Washington, D.C., and being a born and bred American, it’s often not my observations on America that people are interested in. Rather I’m asked, “What is it like in Japan?” After leaving Washington and the daily grind, I’ve been slowly and painstakingly piecing together the fragments of the Asian American experience, which was either completely missing or often regarded as a mostly irrelevant sidebar in American history. But this group’s trajectory in fact fills in a missing chapter that can help make sense of our nation’s origins myth which zigs from the founding fathers who wrote elegiacally of “justice for all” but in a zag officially enshrined the slave trade and ultimately a social hierarchy based on race. We talk about Nativism, but it’s never been about the “native born.” A good look at our naturalization laws show that the all-important factor was “being white” or, as the rulings for exclusion stated, being “not- white.” In their bid to create a white, Christian German empire, we now know that Nazi leaders admired the American Empire and had copied America’s race laws. They regarded the U.S.’s ability to eradicate its indigenous people and create social hierarchy based on race as what they would like to create in Europe. We here in America like to talk about violations of freedom against whites and blacks, but we often fail to register anything other than silent acknowledgement for the passage of legislation after legislation written and passed against those in that legally grey category called “alien” or “non-white.” Perhaps knowing this could be just as instructive as getting acquainted with German and Italian race laws during WWII or watching “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis.”

6 Comments

An American, Chiura Obata. . .

A name or whose art you won’t see at the Whitney. A major retrospective of his work opened at the Smithsonian in November of last year. An artist and friend told me about it, saying “Wow, a must see!” and yet, have you read or heard about it in “the paper of record”? Or seen it in any other major news or cultural coverage? Nor the work of American Ruth Asawa, who dreamed of becoming an art teacher but couldn’t because of laws or discriminatory practices which excluded the ethnically Japanese from all kinds of professions and activities like being a teacher, practicing law or working for the government, etc. As a result of exclusionary race laws, she started her young adult life in “the camps.” Her work is groundbreaking for its organic forms which astound in its simple complexity. She is part of a major retrospective of women’s art at The Art Institute of Chicago, but her link to our understanding of American history is often obscured, this time by Mexico and Modernism. Nor American illustrator Mine Okubo, author of an early graphic novel documenting her experience in a US concentration camp, called “Citizen 13660,” first published 1946 is largely ignored despite today’s graphic novel craze. Or rarely is the work of American writer John Okada (about the No No Boys) included in discussions about race and class in America. . .nor are the poems of American Lawson Fusao Inada. Despite being the Poet Laureate of Oregon, 2006, most educated Americans have never heard of him or his story. Here’s a taste: To This Day Have you ever wondered whatever happened to all the barbed wire that defined and confined the so-called camp at Tule Lake? That’s a good question we have a right to ask as ordinary tax-paying citizens: “Whatever happened to all that barbed wire?” When you think about it, the very idea of fencing such an expanse of land was a daunting challenge for all those concerned because it wasn’t easy to coordinate “back East” planning with “out West” implementation, along with the manufacture and transportation of materials from all points in between. And it was also an innovative undertaking, a historical precedent, because this fence was to confine, not cattle or criminals, but residents of the American West, who, in the western tradition, were to be “rounded up,” and “herded” into fenced areas – Tule Lake being but one such place. Now, thinking about barbed wire, it could be easy to consider related matters that would take us off into a tangent about, oh, fence posts and other such aspects of construction, sidetracking us into thinking about cutting forests for fence posts, and all the effort, energy, expense involved in the overall venture – including catered lunches for planning meetings sequestered in the “red tape” of D.C. – so let’s just focus on the wire that arrived by train on huge spools, I suppose, ready to be unloaded by many men with machines who would then, over days, depending on weather, erect the barbed wire fence. And let’s keep going forward, like the war effort, not backward to the origins of the wire that would include iron ore, iron mines, steel mills, all the sweat, smoke, steam, shoveling, smelting, stamping of the extensive process of manufacturing wire and then barbing it; Yes, let’s keep going forward, like the war effort not backward to the origins of the war, or to the barb wire trenches of the First World War, but to the brand-new barbed wire fence of Tule Lake. The wire was gleaming in the sun! And with all those barbs – thousands upon thousands – all those strands were sparkling! As we can imagine – the fence was really something! And just imagine – from the air, the shining structure may have resembled – a gigantic musical instrument, that storms and raging winds would strum and pluck . . . At any rate, whatever happened to all that barbed wire? It’s all gone somewhere, somehow, obviously, which is a good thing; otherwise, it would pose a hazard for wildlife, and rusted barbs could cause tetanus in humans . . . especially children. So perhaps it’s immaterial to dwell on such material matters like rusted wire of the past; rather, as we can imagine, in this advanced day and age, there just might be a mentality among us, between us, that, to this day, serves to keep us separated serves to keep us confined between “them” and “us,” and this mentality, this condition, invisible as it is, intangible as it is, can actually function like actual barbed wire – and it is up to everyone, in the spirit of humanity, in the name of mutuality, to reach through the strands with extended hands. Lawson Fusao Inada was born in Fresno, California, and as a child during World War II, he was imprisoned in California, Arkansas, and Colorado. His books of poetry include Before the War, Legends from Camp, and Drawing the Line. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, and has served as Poet Laureate of Oregon. Nor did you find the Yellow Bowl Project at the ICP in their “For Freedoms” exhibition a couple of years ago about contemporary photographers' exploration of FDR’s Four Freedoms, nor did any major news outlets write about them, perhaps because they told a different story of Freedom and America than they were ready to share. The tea bowls were the only contemporary work of photography included in the FDR Library‘s year-long exhibition of FDR’s signing of EO 9066 in 2017, when the library was determined to try and tell a more complete story of “the Four Freedoms” back in 2017. Even at NPR. . .where I am not unknown, no one found this interesting enough. Often told that what happened to Japanese Americans was not relevant, "Take it to the Japan Society or the Asia Society" curators and editors would say. Among those who know - the scholars, archivists and experts in the field of immigration and the history of America's race laws written to determine who could and could not participate in this democracy by virtue of whether one was or was “not white”, citizen or not - many want to acknowledge this very American story. It seems it’s the public media that doesn’t. Some say it happened over 75 years ago. Still others say this doesn’t happen in America and didn’t. But it not only happened here, it happened within our lifetimes. It’s important because the cycle continues today. It’s important because the United States is important to the world. We think we have moved forward, but only find that History repeats itself. With this story, American history and its claim that racism ended after the Civil War doesn’t make sense. The ownership of humans may have ended, but exclusion laws took its place. Modeled after the laws to exclude Native Americans, it began 100 years of exclusionary laws written by congress and state and local legislatures around the country against those who were legally deemed by a court of law to be “not white.” It’s the missing link which most public media doesn’t want the public to know. But they shall not erase us. . . is what I say. |

Setsuko WinchesterMy Yellow Bowl Project hopes to spur discussion around these questions: Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? How long do you have to be in the US to be considered a bonafide member of this group? Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed