|

Christine Chang Hanway Below is a Q&A I did with the New York State Writers Institute for Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month. I’ve tried to keep my blogs about history and the facts. This is probably the most personal statement I’ve produced to date. It’s not about the project so much as why I did it. I can’t say it speaks for all Asian Americans, but perhaps my struggle to understand my place in American society faced with issues like race, place, war, peace, justice and injustice might resonate with others. NYS Writers Institute Graduate Assistant Kaori Otera Chen speaks with Setsuko Winchester, the creator of the "Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project," who has also worked as a journalist, editor and producer at NPR’s Morning Edition and Talk of the Nation. Kaori: "I would like us to listen to the stories of the Americans who were excluded from the Four Freedoms, as documented by Setsuko Winchester's 'Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project.' The phone conversation I had with Setsuko was illuminating and made me think deeper about race in America." Visit The Conversation to read Kaori's Q&A with Setsuko.

3 Comments

270 Broadway. One of the sites of the Manhattan Project Manhattan Project Yesterday: Qne usually thinks of Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, Hanford or Trinity when one thinks about the making of the atom bomb. But it wasn't called the Manhattan Project for nothing. (Hint: The Project was started in the 30’s and 40’s in Manhattan, primarily near Columbia University). Here’s the story... https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/30/science/30manh.html Manhattan Project Legacy Today: “In the 75 Years Since Hiroshima, Nuclear Testing Killed Untold thousands.” At the time, the entire Manhattan Project had employed 130,000 people to complete a project that would kill 150,000. This article has a neat graphic showing the race to build a better bomb that followed. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/world/hiroshima-anniversary-nuclear-testing/?utm_campaign=wp_post_most&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&wpisrc=nl_most Despite the moratorium on testing, the project lives on…and there is controversy over how to tell this story, as the National Park Service efforts show. Monuments to the Atomic Age…or the road to our own demise? https://www.npr.org/2017/01/14/508743747/passions-flare-over-memory-of-the-manhattan-project The statue of 12th century Buddhist monk Shinran Shonin, which survived the bombing of Hiroshima, is the only landmark which links Manhattan to this piece of history. Often described as one man’s finger on the button, the Manhattan Project employed 130,000 people in the end. It took many fingers on many buttons to arrive at this end...

Over the years, those who were imprisoned in the ten US war-time concentration camps for US citizens of Japanese ancestry and their descendants began making a pilgrimage to their respective camps in remembrance of what happened in the US back in the 1940’s when a US President, with the flick of a wrist signed into law the single largest forced removal and mass incarceration of US citizens in US history. The act would effectively erase the rights of citizenship and exclude anyone with 1/16th Japanese blood from the protection of the four freedoms promised to everyone anywhere in the world.

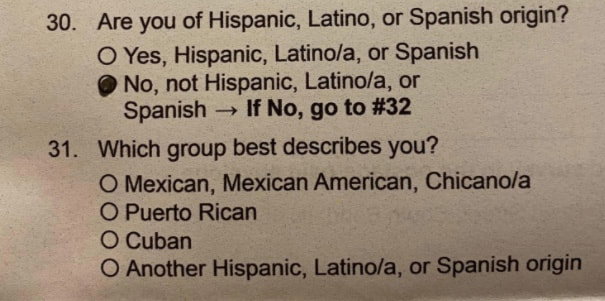

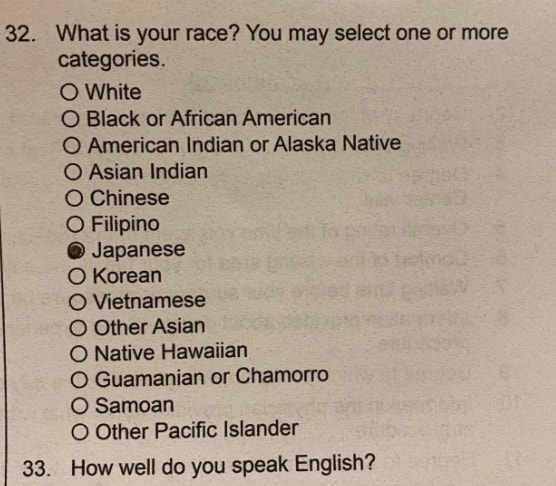

This was to be an important year. It would be 75 years since the camps began closing when those imprisoned would be forced to yet again leave what had become “home” with only what they could carry, 25 dollars and a bus ticket courtesy of the US government to face a possibly hostile world outside the barbed wire fences into an uncertain future. Many who had never been back had been planning to make this journey, some for the first time, for others it was to be their last. However due to Covid 19, all of the annual pilgrimages to the camps were canceled this year. As a result, many of the planners got together, along with the NPS and other historical organizations, to create a Virtual Pilgrimage to the camps. It's a reminder of how easily hard fought freedoms can be lost and that race did matter then and obviously still does today in 2020. There are many stories in America. Most focus on the struggles of "whites" or "African or persons of African descent," the two groups eligible for citizenship as stipulated in the 1870 Naturalization Law established after the Civil War. It would necessitate a whole new group of laws which would govern those who were not 'African" but were also "not white" by law. The Asian American experience falls within this penumbra and I believe is the missing link to understanding race in America. The Virtual Pilgrimage is open to anyone who wants to register. I will be presenting a talk about my Yellow Bowl Project on June 19th, 2020. We can virtually visit all ten of the camps as well as seven other places my tea bowls took me in my examination of this American story. There are many other stories and lesson we can learn while the pilgrimage lasts, from June 13 until August 16, 2020. Here is a ink to the complete schedule and registration information for the Virtual Pilgrimage. FYI, I’ve finally created a twitter account, @SetsukoWinches1, if you’d like to share. Hope you find it interesting! I was recently asked to fill out the following form asking about my racial and ancestral background after a medical eye procedure in NY.

The list seems completely random but here are a few more I thought I’d randomly add: 35. Are you white? Which group best describes you? Germanic, Arabic, Slavic, Celtic, Scandinavian, or Other? If yes to any of the above, go to 36: 36. What is your race? You may select one or more categories.

37. How well do you speak any other language than English? If only English, what kind of English dialect do you speak?

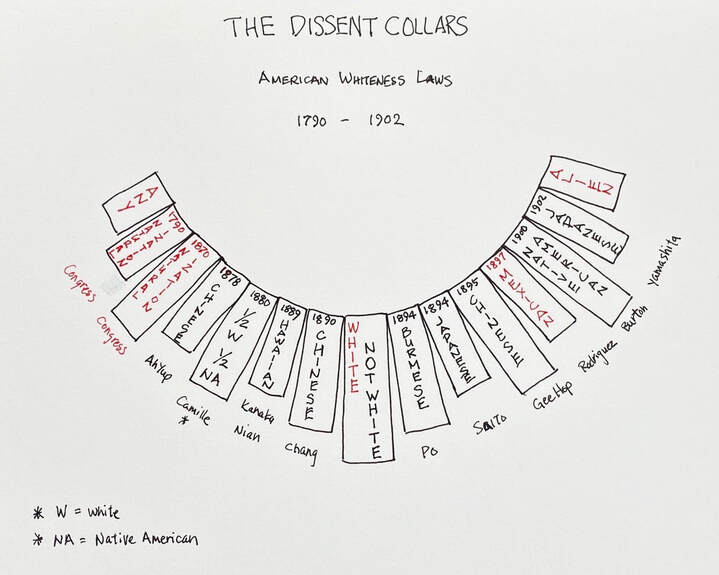

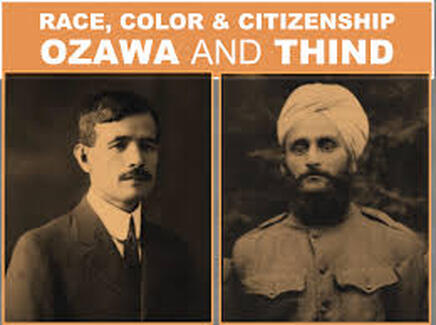

Thank you for participating in our survey. Hope you will turn to us again when next you need to fill an urgent healthcare need. A New Work in Progress... Part Two of my conceptual art project, which explores "what it means to be an American," is now available to view on my website. Called "THE DISSENT COLLARS," Part Two focuses on what I call "American Whiteness Laws," or race prerequisite laws, and deals with how US courts and legislators created a new category of immigrants in the late 1800's labeled "aliens ineligible to naturalize," because they were neither from Africa nor found to be "White" by law. To get a taste of how these laws worked, here's a short essay I was asked to write for The Washington Spectator. It's a history of California's race laws entitled "The Dark Side of Sunny California." I recently wrote the essay below for my local Massachusetts paper, The Sandisfield Times, at the encouragement of the editor, Bill Price. The essay examines many of the laws that lie outside the strictly Black/White paradigm to bring focus to the lesser known grey area of law which governed those who are legally “not-White”. Out on the Limb of History...When Most Asians Disappeared The report about the Sandisfield Arts Center’s 2019 program last month was a lively column about how

Sandisfield’s Art Center strives to educate us about “Our Town,” our constitution, and our history. Featured were “Stimulating and timely talks from our scholars Bill Cohn and Val Coleman (Val paid for copies of the U.S. Constitution at his inspiring and passionate lecture, ‘The Constitution Alive’) and Dr. Robert Maryks presented ‘Fascism and Racial Laws in Italy’ (preceded by a free showing of ‘The Garden of the Finzi-Continis’).” It’s good that we learn the history of fascism and race laws around the world and re-examine what the constitution says, but shouldn’t we also learn about one of the most legally racist periods in US history – the post-Civil War/Reconstruction era between the 1880s and 1940s? During this period, when the U.S. was opening vast swaths of territory to “settle,” hundreds of local, state, and federal laws were written and passed which would legally define who could and who could not become an American and thus receive constitutional protections as well as participate fully in our country’s democracy. Back then it was a white minority fearing being overwhelmed by a non-white majority. During that time a fearful electorate passed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, banning further immigration from China. This act would inspire the creation of a new federal agency, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which became a new arm of government created to enforce the new exclusion act. A quick look at U.S. race laws that followed show that “not white” was chosen as the quick and easy way to separate the chaff from the desired “all-American” wheat. Those who did not fit in with this paradigm were left to fight it out through the courts which, more often than not, ignored the constitution’s call for liberty and justice for all and instead confirmed and expanded this country’s racially-based caste system, cementing it firmly into the laws of the land. Most discussions on race today remain limited to a white/black paradigm but it’s the hundreds of laws targeting other “non-white” peoples passed after the Civil War which still linger. Their effects continue to enliven our political discourse today. While many of us in this country come from Europe, many of us did not. Many were already here and had a different row to hoe towards “freedom, liberty, opportunity, and justice.” In fact, it was post-1880s that a whole new category of human beings was slowly shaped, molded, and defined by the rule of law – those deemed to be “Aliens ineligible to naturalize.” (This would not include my husband, who is white, British, Christian, and an immigrant, but would have – had I not been born here – excluded me.) These laws were all based on the 1790s Naturalization Act – which stated that “Any Alien”... being a ‘free white person’... having had residency for two years ... was of good character ... could naturalize.” The phrase “Any Alien,” of course, excluded native born Native Americans, the first to be excluded. And a look at the long history of “Exclusion” laws shows how important that one adjective, “white,” written into that early law by the founding fathers helped to tint the color of our laws and our citizenry ever whiter for nearly 150 years. What we’re seeing today is less “Garden of the Finzi-Continis” and more a continuation of the Page Act of 1875, the Dawes Act of 1887, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. And In re Saito, 1894, was the first law passed in the U.S. to specifically exclude persons of Japanese ethnicity from becoming an American citizen, the court having ruled that because Mr. Saito was “not white” he was ineligible to naturalize. By 1922, it would become a federal law (Ozawa v. US) with the Supreme Court’s ruling that a Japanese person was “not white,” therefore could not be a naturalized citizen. As a resident of the Berkshires, it was a bittersweet realization for me to discover that the Saito ruling was made in a district court right here in my adopted state of Massachusetts. The legal rationales were congressional intent, common knowledge, scientific evidence, and legal precedent. Maybe that’s why even after having gotten a graduate degree in Journalism from NYU, worked for 10 years as a journalist at NPR headquarters in Washington, D.C., and being a born and bred American, it’s often not my observations on America that people are interested in. Rather I’m asked, “What is it like in Japan?” After leaving Washington and the daily grind, I’ve been slowly and painstakingly piecing together the fragments of the Asian American experience, which was either completely missing or often regarded as a mostly irrelevant sidebar in American history. But this group’s trajectory in fact fills in a missing chapter that can help make sense of our nation’s origins myth which zigs from the founding fathers who wrote elegiacally of “justice for all” but in a zag officially enshrined the slave trade and ultimately a social hierarchy based on race. We talk about Nativism, but it’s never been about the “native born.” A good look at our naturalization laws show that the all-important factor was “being white” or, as the rulings for exclusion stated, being “not- white.” In their bid to create a white, Christian German empire, we now know that Nazi leaders admired the American Empire and had copied America’s race laws. They regarded the U.S.’s ability to eradicate its indigenous people and create social hierarchy based on race as what they would like to create in Europe. We here in America like to talk about violations of freedom against whites and blacks, but we often fail to register anything other than silent acknowledgement for the passage of legislation after legislation written and passed against those in that legally grey category called “alien” or “non-white.” Perhaps knowing this could be just as instructive as getting acquainted with German and Italian race laws during WWII or watching “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis.” An American, Chiura Obata. . .

A name or whose art you won’t see at the Whitney. A major retrospective of his work opened at the Smithsonian in November of last year. An artist and friend told me about it, saying “Wow, a must see!” and yet, have you read or heard about it in “the paper of record”? Or seen it in any other major news or cultural coverage? Nor the work of American Ruth Asawa, who dreamed of becoming an art teacher but couldn’t because of laws or discriminatory practices which excluded the ethnically Japanese from all kinds of professions and activities like being a teacher, practicing law or working for the government, etc. As a result of exclusionary race laws, she started her young adult life in “the camps.” Her work is groundbreaking for its organic forms which astound in its simple complexity. She is part of a major retrospective of women’s art at The Art Institute of Chicago, but her link to our understanding of American history is often obscured, this time by Mexico and Modernism. Nor American illustrator Mine Okubo, author of an early graphic novel documenting her experience in a US concentration camp, called “Citizen 13660,” first published 1946 is largely ignored despite today’s graphic novel craze. Or rarely is the work of American writer John Okada (about the No No Boys) included in discussions about race and class in America. . .nor are the poems of American Lawson Fusao Inada. Despite being the Poet Laureate of Oregon, 2006, most educated Americans have never heard of him or his story. Here’s a taste: To This Day Have you ever wondered whatever happened to all the barbed wire that defined and confined the so-called camp at Tule Lake? That’s a good question we have a right to ask as ordinary tax-paying citizens: “Whatever happened to all that barbed wire?” When you think about it, the very idea of fencing such an expanse of land was a daunting challenge for all those concerned because it wasn’t easy to coordinate “back East” planning with “out West” implementation, along with the manufacture and transportation of materials from all points in between. And it was also an innovative undertaking, a historical precedent, because this fence was to confine, not cattle or criminals, but residents of the American West, who, in the western tradition, were to be “rounded up,” and “herded” into fenced areas – Tule Lake being but one such place. Now, thinking about barbed wire, it could be easy to consider related matters that would take us off into a tangent about, oh, fence posts and other such aspects of construction, sidetracking us into thinking about cutting forests for fence posts, and all the effort, energy, expense involved in the overall venture – including catered lunches for planning meetings sequestered in the “red tape” of D.C. – so let’s just focus on the wire that arrived by train on huge spools, I suppose, ready to be unloaded by many men with machines who would then, over days, depending on weather, erect the barbed wire fence. And let’s keep going forward, like the war effort, not backward to the origins of the wire that would include iron ore, iron mines, steel mills, all the sweat, smoke, steam, shoveling, smelting, stamping of the extensive process of manufacturing wire and then barbing it; Yes, let’s keep going forward, like the war effort not backward to the origins of the war, or to the barb wire trenches of the First World War, but to the brand-new barbed wire fence of Tule Lake. The wire was gleaming in the sun! And with all those barbs – thousands upon thousands – all those strands were sparkling! As we can imagine – the fence was really something! And just imagine – from the air, the shining structure may have resembled – a gigantic musical instrument, that storms and raging winds would strum and pluck . . . At any rate, whatever happened to all that barbed wire? It’s all gone somewhere, somehow, obviously, which is a good thing; otherwise, it would pose a hazard for wildlife, and rusted barbs could cause tetanus in humans . . . especially children. So perhaps it’s immaterial to dwell on such material matters like rusted wire of the past; rather, as we can imagine, in this advanced day and age, there just might be a mentality among us, between us, that, to this day, serves to keep us separated serves to keep us confined between “them” and “us,” and this mentality, this condition, invisible as it is, intangible as it is, can actually function like actual barbed wire – and it is up to everyone, in the spirit of humanity, in the name of mutuality, to reach through the strands with extended hands. Lawson Fusao Inada was born in Fresno, California, and as a child during World War II, he was imprisoned in California, Arkansas, and Colorado. His books of poetry include Before the War, Legends from Camp, and Drawing the Line. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Guggenheim Foundation, and has served as Poet Laureate of Oregon. Nor did you find the Yellow Bowl Project at the ICP in their “For Freedoms” exhibition a couple of years ago about contemporary photographers' exploration of FDR’s Four Freedoms, nor did any major news outlets write about them, perhaps because they told a different story of Freedom and America than they were ready to share. The tea bowls were the only contemporary work of photography included in the FDR Library‘s year-long exhibition of FDR’s signing of EO 9066 in 2017, when the library was determined to try and tell a more complete story of “the Four Freedoms” back in 2017. Even at NPR. . .where I am not unknown, no one found this interesting enough. Often told that what happened to Japanese Americans was not relevant, "Take it to the Japan Society or the Asia Society" curators and editors would say. Among those who know - the scholars, archivists and experts in the field of immigration and the history of America's race laws written to determine who could and could not participate in this democracy by virtue of whether one was or was “not white”, citizen or not - many want to acknowledge this very American story. It seems it’s the public media that doesn’t. Some say it happened over 75 years ago. Still others say this doesn’t happen in America and didn’t. But it not only happened here, it happened within our lifetimes. It’s important because the cycle continues today. It’s important because the United States is important to the world. We think we have moved forward, but only find that History repeats itself. With this story, American history and its claim that racism ended after the Civil War doesn’t make sense. The ownership of humans may have ended, but exclusion laws took its place. Modeled after the laws to exclude Native Americans, it began 100 years of exclusionary laws written by congress and state and local legislatures around the country against those who were legally deemed by a court of law to be “not white.” It’s the missing link which most public media doesn’t want the public to know. But they shall not erase us. . . is what I say. Many iconic things that we now associate with Fascist Germany ironically had its roots in America and Britain, or at least not in Germany. I have four here to share. 1. The Nazi Salute/Bellamy Salute This photo, taken in the 1940’s by photographer Hansel Mieth, depicts Japanese Americans imprisoned at the Heart Mountain Relocation Camp in Wyoming using the Bellamy salute in the Pledge of Alliegiance. It was named after Francis Bellamy, the author of the Pledge of Allegiance. The inventor of the Bellamy salute was James B. Upham, junior partner and editor of The Youth's Companion.

The Bellamy salute was first demonstrated on October 12, 1892, according to Bellamy's published instructions for the "National School Celebration of Columbus Day": At a signal from the Principal, the pupils, in ordered ranks, hands to the side, face the Flag. Another signal is given; every pupil gives the flag the military salute—right hand lifted, palm downward, to align with the forehead and close to it. Standing thus, all repeat together, slowly, “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands; one Nation indivisible, with Liberty and Justice for all.” At the words, “to my Flag,” the right hand is extended gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side. — From The Youth’s Companion, 65 (1892): 446–447 2. Concentration Camps Before the Germans used them to first control Jewish populations in Germany, this tool of empire was used in these conflicts: 1898: The Spanish Imprisonment of Cubans during the Spanish American War 1899 – 1902: British had white and black concentration camps during the Anglo Boer Wars 1899 – 1902: US used them against the Filipinos during the Philippine-American War 1904 – 1908: Germany used concentration camps and created their first death camps against Namibians Historically, concentration camps were used to concentrate and imprison a particular group of people because of who they were, not what they did. 3. The Nuremberg Laws The inspiration for the Nazi regime's Nuremberg Laws, created to separate the Jews from German society, was ironically America’s Jim Crow Laws. One of the biggest ironies of WWII was that the FDR Administration created a segregated African-American unit to help fight for freedom in Europe, only for those soldiers to return to Jim Crow Laws back home. The segregated all-Japanese American military troops faced a similar situation when they went to fight for freedom in Europe while their families were imprisoned in US concentration camps back home. 4. The Eugenics Movement It might surprise people that, rather than Germany, the eugenics movement has its origins in England and was the brainchild of Darwin’s half-cousin Francis Galton, the man who coined the term in 1883. The American eugenics movement had a strong following in the US, with many prominent followers and was practiced for many years before it took hold in Germany. Read more... Trying to promote "good" genes sounds reasonable conceptually, but when you label something good, then is there a bad? And who gets to decide those values? Many people ask me: "Why would major news outlets, historic institutions, museums and academia have a problem with your project?" Here is an excerpt from the BBC coverage of Trump's UK State Visit, June 3, 2019. Trump Reads Roosevelt Prayer During a radio message, President Roosevelt led the nation in a prayer ahead of the D-Day landings. President Trump takes to the stage to read the same prayer:

It was a crusade. For freedom? And for whom?

I guess people like Trump. According to the BBC: The Queen and the Prince of Wales attended the commemorations on Southsea Common, along with representatives from the countries that fought alongside the UK in the Battle of Normandy including French President Emmanuel Macron, US President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Also attending were German Chancellor Angela Merkel, as well as leaders from Australia, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Poland and Slovakia. Many Japanese Americans fought in Europe during WWII, recruited or drafted out of US concentration camps, Native Americans out of reservations and Blacks from a Jim Crow South. My Freedom from Fear project was excluded, despite being told repeatedly my work was in the show, from The New York Historical Society, CUNY's Roosevelt House, sidelined at The Ford Museum and removed from The George Washington University Museum. I was told my work would not be included in the Four Freedoms exhibition in France at The Memorial de Caen, in Caen, France. The last time the tea bowls visited the nation’s capital was in June of 2016. They visited two places. First, they got to hang out at the steps of the Supreme Court for a bit. While I was setting up, many curious passersby asked what I was doing with all these yellow bowls. As there were many lawyers in the area, some actually remembered hearing about one of the four cases I was showcasing: Fred Korematsu v. United States, Gordon Hirabayashi v. United States, Yasui v. United States and Ex parte Endo. However, the majority of them, tourists, had no idea. The funniest reaction I received was from a young black man and his mother who lived locally, in Washington, DC. They were watching me set up for a while and finally had the courage to interrupt and ask what I was doing. When I told them the story of the forced removal and mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, the young man turned to his mother and said, “Did you know this?” His mother shook her head and said quietly, no. Then he turned to me and said, “That happened in America??? No sh--!!!” We all broke out laughing. Here’s a link to an earlier blog if you want to know more about that image. After taking that image and repacking everything, we moved over to the second spot...The Memorial to Japanese-American Patriotism which is part of the National Parks Service. It’s just a five-minute walk from Union Station. The small park with the beautiful water feature shown at the top tells the story of American men, women and children of Japanese ethnicity and their immigrant parents who were imprisoned in ten US concentration camps in the deserts and swamps of the American west and Midwest. Carved into the stone next to the pool are the words “Here We Admit a Wrong.” It was so peaceful and quiet, with very few visitors, that in an appropriately ironic twist, it had become a popular napping spot for homeless people (as you can see in the top image if you look carefully). Ten panels line the wall of the Memorial adjacent to the pool, each with the names of the camps and the number of individuals who were imprisoned. At the center is the sculpture of a bird, a crane, entangled in barbed wire. It’s also a memorial to the Japanese-American men and women, many of whom were recruited from these American camps, who went to fight for the four freedoms abroad, but also to win freedom for those family members who remained imprisoned at home.

The 442nd and 100th Battalion, a segregated Japanese-American military fighting unit, would become the most decorated unit of its size and duration in US military history. The unit was awarded: 9486 Purple Hearts 4000 Bronze Stars 560 Silver Stars 29 Distinguished Service Crosses 21 Medals of Honor 7 Presidential Unit Citations 800 were killed/or missing in action. 6,000 would serve in the Military Intelligence Service as translators and interpreters, and others would serve in the nurses’ corps. In the end, its said that about 33,000 would go on to serve in the US armed forces during WWII. Now, to today. As of this month, the Yellow Bowls, represented by one of the images from the Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project, can be found at the George Washington University/Textile Museum, part of an exhibition called “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms,” which opened in Washington, DC, on February 13, 2019. Here’s a link to an article in the Berkshire Eagle announcing the opening of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedom’s paintings depicting FDR’s 1941 Four Freedoms speech. Essentially, the exhibition is split into two. The main floor depicts much of the commercial and propaganda art that the illustrator Norman Rockwell produced for magazines and the government leading up to and during WWII. In 1943, Norman Rockwell was paid to illustrate FDR’s Four Freedoms for the Saturday Evening Post. His depictions met with little fanfare at first. But they would eventually become iconic after the Post and the US Department of the Treasury teamed up to sponsor a two-year touring exhibition of the paintings, exhibiting them around the nation, as a way to promote American patriotism and the sale of war bonds. On the second level of the museum is a non-commercial contemporary take on those Freedoms. The gallery here is filled with art that questions how universal those freedoms were and are today—but from the perspective of those who were denied those freedoms. They include images from Norman Rockwell, himself, who had advocated for Black Civil Rights and the “Right to Know” during the Vietnam War. My contribution to the story of the Four Freedoms should be in this section...Let me know if you find it! |

Setsuko WinchesterMy Yellow Bowl Project hopes to spur discussion around these questions: Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? How long do you have to be in the US to be considered a bonafide member of this group? Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed