|

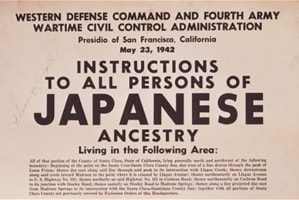

The Supreme Court officially overturned the wrongful 1944 ruling on Korematsu vs. the US this week (Tuesday, June 26, 2018), but cleared the way for an ethnically based Travel Ban which hints of 1882 and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Justice John Roberts acknowledges the wrongful use of concentration camps to imprison US citizens on the basis of race and officially overturns the offending law with the following phrase: “Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority,” Roberts wrote. “But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission.” Here’s the complete story. While it corrected a 74-year-old wrong, it replaced one long held injustice with another by legalizing the use of a travel ban on an entire ethnic group or country, echoing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The passage of that law would usher in a host of exclusionist laws targeting people of Chinese ancestry in this country, then Japanese immigrants and their children and eventually to all Asians in general. While most laws have been repealed or been canceled out by other laws, the fact that Korematsu remained technically on the books until this past Tuesday means discriminatory actions taken against Asian peoples have been not just accepted but ambiguously legal for over 130 years. This is probably why the Asian American experience is seldom included in discussions about the history of American Jurisprudence because it was legal. I was recently invited to participate on a panel discussion on WAMC—my local NPR Station—about immigration, to ask the question which is at the heart of my project…Who is an American? And what does citizenship mean? While that question and its answer may be clear for some in the eyes of the US government, it has not always been so straightforward for folks who looked like me and my family. On another related note, documentary filmmaker Vivienne Shiffer, who grew up in the community adjacent to one of the two concentration camps located in Arkansas and produced the film, Relocation, Arkansas, the Aftermath of the Incarceration, sent me this report from the Arkansas Times: [One clarification that needs to be made—this proposed site is not 5 miles from the Rohwer Camp site: it is not only adjacent to it, 160 acres of the proposed site is land that actually comprised part of the Rohwer Camp.] Proposed child holding site in Arkansas 5 miles from WWII Japanese-American internment camp Posted By Benjamin Hardy on Thu, Jun 21, 2018 at 2:39 PM THV 11 reports that the Trump administration is considering a piece of property in the unincorporated Desha County community of Kelso in its search for sites to house immigrant children forcibly separated from their parents at the border. Kelso is about a five-minute drive away from the Rohwer internment camp at which over 8,000 Japanese-Americans — many of them children — were held captive by their own government during World War II.

Here’s the link to the rest of the article. Hope you find it interesting!

0 Comments

image: Edel Rodriguez Whether we like to admit it or not, being white, and a man matters in the United States and that’s because early on in the establishment of this country, the rules of naturalization and who could become a citizen (and therefore vote) was codified into law in one of the first pieces of legislation passed by the nascent US congress in the Naturalization Act of 1790, which said that citizenship was restricted to “any alien, being

a free white person” who had been in the US for two years. “Any Alien” was stipulated to exclude Native Americans. The politics of “exclusion” was always at the heart of this new country, although at the same time and ironically it's leaders preached Justice for All. We can now see that they meant Justice for all aliens...but only if they are men, and only if they are white and for good measure, only if they had been here for two years. These words and stipulations have changed over the decades, like the two years to three or more, or to include aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent in 1870. But what about Asians and Asian Americans? I could not have answered that question six years ago. But I can now. What’s most instructive about the Asian American experience today is that it shows how easily hard-won rights can be lost and that the issues of discrimination are not necessarily divided along republican vs. democrat, conservative vs. liberal or even black vs. white. Below is an excerpt from an essay I was asked to write about this aspect of US history for The Washington Spectator. I hope you find it interesting: I recently went to Ellis Island on a beautiful spring morning and spent a couple of hours by myself watching the light pour into the Great Hall before the museum opened to the public. I was there to arrange the most recent iteration of an art project I’ve been working on for several years, this one having to do with an historic event that happened at Ellis Island back in 1942 and a related incident in 1998. To be there all these years later, knowing what I know now, was as if someone had firmly screwed in a light bulb that had been left loose, finally illuminating a part of my story and that of an America that I had never known or fully understood. I was born and bred in the United States and grew up in the 1960s. My immigrant parents, by any standard, had achieved the American dream, with a successful small business in New York City and a middle-class home in the New Jersey suburbs. Like most of our European immigrant neighbors, I felt we were a healthy part of this “melting pot” we called America. My father, out of gratitude for his new country, always drove an American car, a Buick Le Sabre for him and a Dodge Dart for my mother, followed by successive generations of GMs, Chryslers and Fords over the years, despite the fact that many of our neighbors were starting to buy Japanese cars in the ’70s and German ones in the ’80s. My father taught us to appreciate the diversity and generosity of this country, and I remember the pride and excitement I felt being taken to see the Statue of Liberty as a youngster. As we stood on the windswept deck of the ferry, I imagined my parents as part of the great wave of people who were welcomed into the arms of this beckoning green lady. What I did not know at the time was that when my father first arrived, he was not allowed to stay in this country. That’s because he was Asian and, in particular, Japanese. I did not know, growing up, that Japanese people had been banned from immigrating to America, a ban that was in place nominally from 1907 and definitively, with the Asian Exclusion Act (which banned all Asians), in 1924, and wouldn’t truly be lifted until 1965... You can read the rest of the essay The Washington Spectator. To learn more about the Ellis Island Exhibit in 1998, click here. |

Setsuko WinchesterMy Yellow Bowl Project hopes to spur discussion around these questions: Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? How long do you have to be in the US to be considered a bonafide member of this group? Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed