|

The last time the tea bowls visited the nation’s capital was in June of 2016. They visited two places. First, they got to hang out at the steps of the Supreme Court for a bit. While I was setting up, many curious passersby asked what I was doing with all these yellow bowls. As there were many lawyers in the area, some actually remembered hearing about one of the four cases I was showcasing: Fred Korematsu v. United States, Gordon Hirabayashi v. United States, Yasui v. United States and Ex parte Endo. However, the majority of them, tourists, had no idea. The funniest reaction I received was from a young black man and his mother who lived locally, in Washington, DC. They were watching me set up for a while and finally had the courage to interrupt and ask what I was doing. When I told them the story of the forced removal and mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, the young man turned to his mother and said, “Did you know this?” His mother shook her head and said quietly, no. Then he turned to me and said, “That happened in America??? No sh--!!!” We all broke out laughing. Here’s a link to an earlier blog if you want to know more about that image. After taking that image and repacking everything, we moved over to the second spot...The Memorial to Japanese-American Patriotism which is part of the National Parks Service. It’s just a five-minute walk from Union Station. The small park with the beautiful water feature shown at the top tells the story of American men, women and children of Japanese ethnicity and their immigrant parents who were imprisoned in ten US concentration camps in the deserts and swamps of the American west and Midwest. Carved into the stone next to the pool are the words “Here We Admit a Wrong.” It was so peaceful and quiet, with very few visitors, that in an appropriately ironic twist, it had become a popular napping spot for homeless people (as you can see in the top image if you look carefully). Ten panels line the wall of the Memorial adjacent to the pool, each with the names of the camps and the number of individuals who were imprisoned. At the center is the sculpture of a bird, a crane, entangled in barbed wire. It’s also a memorial to the Japanese-American men and women, many of whom were recruited from these American camps, who went to fight for the four freedoms abroad, but also to win freedom for those family members who remained imprisoned at home.

The 442nd and 100th Battalion, a segregated Japanese-American military fighting unit, would become the most decorated unit of its size and duration in US military history. The unit was awarded: 9486 Purple Hearts 4000 Bronze Stars 560 Silver Stars 29 Distinguished Service Crosses 21 Medals of Honor 7 Presidential Unit Citations 800 were killed/or missing in action. 6,000 would serve in the Military Intelligence Service as translators and interpreters, and others would serve in the nurses’ corps. In the end, its said that about 33,000 would go on to serve in the US armed forces during WWII. Now, to today. As of this month, the Yellow Bowls, represented by one of the images from the Freedom from Fear/Yellow Bowl Project, can be found at the George Washington University/Textile Museum, part of an exhibition called “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms,” which opened in Washington, DC, on February 13, 2019. Here’s a link to an article in the Berkshire Eagle announcing the opening of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedom’s paintings depicting FDR’s 1941 Four Freedoms speech. Essentially, the exhibition is split into two. The main floor depicts much of the commercial and propaganda art that the illustrator Norman Rockwell produced for magazines and the government leading up to and during WWII. In 1943, Norman Rockwell was paid to illustrate FDR’s Four Freedoms for the Saturday Evening Post. His depictions met with little fanfare at first. But they would eventually become iconic after the Post and the US Department of the Treasury teamed up to sponsor a two-year touring exhibition of the paintings, exhibiting them around the nation, as a way to promote American patriotism and the sale of war bonds. On the second level of the museum is a non-commercial contemporary take on those Freedoms. The gallery here is filled with art that questions how universal those freedoms were and are today—but from the perspective of those who were denied those freedoms. They include images from Norman Rockwell, himself, who had advocated for Black Civil Rights and the “Right to Know” during the Vietnam War. My contribution to the story of the Four Freedoms should be in this section...Let me know if you find it!

2 Comments

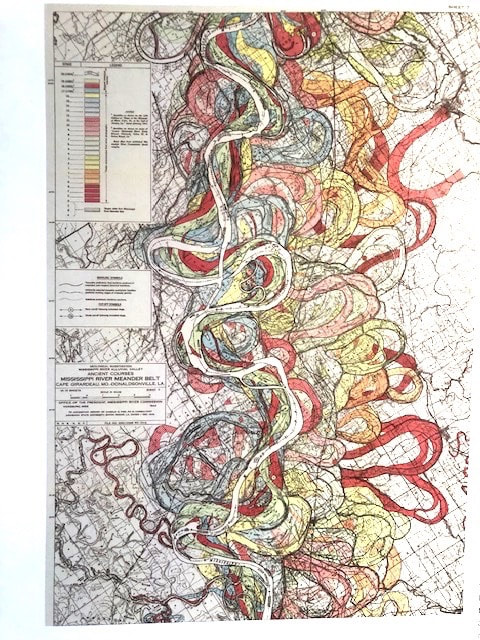

On a recent trip down the Mississippi River from its source in Lake Itasca in Minnesota to where it debouches into the Gulf of Mexico near Venice, Louisiana, I discovered that following the river reveals a more complete and complex story of race and the racial fault lines that divide this country than the one told along the Mason-Dixon Line. Starting from the top, stories of broken treaties, genocide and the forced removal of American Indians dot the river on both sides up and down, the main law being the Indian Removal Act of 1830 which essentially made the entire river the demarcation line for this federal policy. In the middle, the grave of Dred Scott lies on the Missouri side of the Mississippi at the Calvary Cemetery and Mausoleum in St. Louis. In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court ruled that no person of African descent could claim US citizenship, thus freedom, despite having lived for four years outside of Missouri, in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal. Just across the river, the remains of the Cahokia Mounds Indian Civilization, an urban center as big as London which existed in the 13th century and considered one of great cities of the world by archeologists, lies virtually unknown on the Illinois side. Further down the river into Tennessee, you will find The Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, the site where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated as he stood on the balcony on April 4, 1968 at 6:01pm, CST. Move a bit further down and back onto the Arkansas side of the river and you will find two of America’s concentration camps, which imprisoned nearly 17,000 US citizens of Japanese ethnicity during WWII in the towns of Rohwer and Jerome. As a result, the two briefly became the 4th and 5th largest cities in the state. Smack in the middle of the two camps, which are located 26 miles apart from each other, is a museum dedicated to telling the story of what happened there in the town of McGehee. Another story, as you follow the flow of the river out into the gulf from Venice, LA, is the ironic story of Cat Island, Mississippi, where the US military used dogs to conduct a secret experiment on Japanese American soldiers during WWII in the misguided belief that “Japanese” smelled different from other human beings. It didn’t work. The dogs attacked whites just as viciously. On a side trip to Oklahoma, we learned about one of the earliest Native American Civil Rights leaders in the country in the case Standing Bear v. Crook. The ruling established for the first time, in 1879, that Native Americans were human beings. The case was tried in Omaha, Nebraska, on the Missouri River, a tributary of the Mississippi. The struggle to be recognized as human, as well as the right to naturalize and become a citizen and have one’s needs and one’s contributions known, is without a doubt more varied in hue along the Mississippi than the black and white, North and South, struggle most Americans learn. Much of what is happening today with US citizens being detained just for speaking Spanish, or Vietnamese, who were given refugees status at the end of the Vietnam War, being deported after 40 years in this country, has at its core the question, “Who is an “American?” This brings us to the 1790’s Naturalization Act, one of the earliest laws passed by the new continental congress, which established who was eligible to naturalize and thus become an American. It stated that “Any Alien” being a white person…who had residency in this country for two years and was of good character, could become a US citizen. In other words, the first exclusion was the native born…Native Americans. It has been used many times to exclude entire groups of peoples. As I learn more about my country, I see how little many of us, including myself, know about this place we call America and about each other. We, on the East Coast of the country, probably know more about what happened to Europeans in Europe than we know about the formation of the United States and the laws that keep this experiment going. Prejudice, bias and discrimination will always exist, but if it is codified into law, it becomes a form of eugenics. If we are to remain a country based on the rule of law, dedicated to a just and equal world, the only way to achieve that is not only to have our laws reflect that goal but that those laws be equally applied. Drug laws that incarcerate African Americans who use, but provide rehab for whites, is an unequal application of the law. A recent poll shows that 40% of Americans believe that no American Indians are alive and in existence in America today. This prompts the question, if no one hears you, do you still exist in a representative democracy? This poll seems to suggest that the answer is No. Perhaps the Mississippi River and the story it tells of American racial apartheid and the fight to be included could help change all that. |

Setsuko WinchesterMy Yellow Bowl Project hopes to spur discussion around these questions: Who is an American? What does citizenship mean? How long do you have to be in the US to be considered a bonafide member of this group? Archives

June 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed